Dutch the store

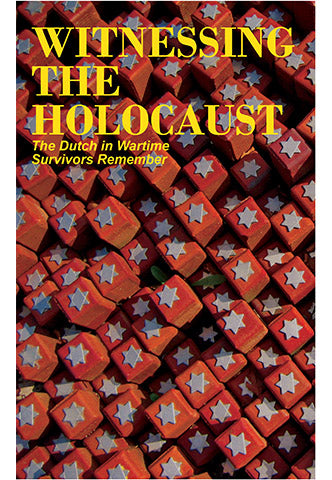

Witnessing the Holocaust

Couldn't load pickup availability

The Dutch in Wartime: Survivors Remember is a series of books with wartime memories of Dutch immigrants to North America, who survived the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands.

In Book 3: Witnessing the Holocaust, sixteen writers tell us how Dutch Jews were dragged from their homes to be murdered in Nazi death camps. We read first-hand accounts of friends disappearing, of betrayal and its dreadful consequences and of the torment of life in Nazi concentration camps.

Designed and written to be easily accessible to readers of all ages and backgrounds, these books contain important stories about the devastating effects of war and occupation on a civilian population.

Edited by Tom Bijvoet.

97 pages

Historical background, 2 maps and 16 wartime memories.

ISBN: 978-0-3968308-4-6

On the cover: ‘102,000 Bricks’, monument by J.A. Gilbert and P.A. Ritmeijer remembering the 102,000 people incarcerated in Westerbork concentration camp who perished during the war. (Photo: Bert Kaufmann)

READ AN EXCERPT

The war will never be over

Like all Jewish children I was excluded from regular school. I had to go to a Jewish school which was not a day school or religious school as we now know it, but a school where only Jewish children went and only Jewish teachers taught. We were taught the usual things, of course, but also a few very important things which are not normally taught. First, when we came into class in the morning, the teacher would check that we all had a yellow star. If a child did not have one, they had to borrow a sweater or some other garment from another child. That was illegal, but at least everybody wore a star. The next lesson was: “What would you say if a soldier came into the class and asked you at what time your parents came home last night?” The answer had to be ‘before 8.00 p.m.’ (curfew hour) of course, but not too close to it. Something like 7.30 p.m. or 6.15 p.m., so that it would sound like the truth.

As Jews, we were not allowed to go to the movies or the public swimming pool, sit on park benches, play in the park, own radios, shop at any time except between three and five o’clock in the afternoon, go to plays, concerts or even the circus. We were not allowed to use public transit. Jewish men lost their jobs; they were not allowed to be journalists, symphony conductors, doctors, lawyers and many other professions. And of course we also had the curfew, as mentioned. We were not allowed to be out on the street between eight o’clock at night and six o’clock in the morning.

(…)

On June 20, 1943, when I had just turned ten years old, there was a big round-up in all of Amsterdam. The Germans came at about nine o’clock in the morning and chased us out of our apartment and down to the street. Many people were standing in the street and hanging out of windows, watching what was going on. Not everybody was hostile though. I remember clearly how Mrs. Gijtenbeek, the lady who owned the corner grocery store came to me with a small bag in her hand. In the bag were sweets that she wanted to give me. She had always been very nice to the neighborhood children and after the invasion she was even nicer to me than before.

We were taken to one of the big squares in Amsterdam and there we were made to wait. For what? We didn’t know. We waited all morning. Finally, at about noon, we were taken to Central Station in Amsterdam. There, we were shoved into the cattle cars, packed in so tight that there was hardly room to breathe. We arrived in Westerbork, a concentration camp in the northeast of Holland, at about eleven o’clock at night and were sent through the wooden gates to one of the barracks where we had to register and undergo a medical examination. Then we were assigned to a barracks.

(…)

Six months after our arrival in Westerbork, in January of 1944, we were deported to a concentration camp in what was then Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). It was called Theresienstadt, the Czech name is Terezin. That trip took us two days in cattle cars. Again, we were housed in barracks, this time built out of stone. Theresienstadt was an old garrison town, built in 1780, for about 7000 soldiers and their families. The barracks were square, with a sort of small outside yard in the middle of the square. In the center of that yard stood a hand pump where we got our water. There were washrooms, but the water there was turned off for several hours every day. The water was rusty and smelled bad. Theresienstadt sits on marshy ground and the water came from the marsh.

(…)

Beginning in October of 1944, all children aged ten years and over, also had to work. My first job was as a message carrier for the Siechenhaus, the house for the old and sick. That was my ‘regular’ job. I was also assigned to a number of other jobs, one of which was passing cardboard boxes from one child to another, to a third, and so on, in a line. Only children were assigned to this particular work. Our line led from the crematorium to a waiting truck – though I didn’t know that then. The boxes contained the ashes of the dead. The dead could not be buried, because as a result of the marshy ground, water would seep into the graves. So they were cremated. We children knew that full well, because we knew pretty much everything that went on and also because the boxes were ill-made and their covers did not quite fit. Ashes and bits of bone would seep out. The boxes had names on them as well, though I did not and do not know why. The waiting truck eventually went to the river Eger which flows past Theresienstadt and there the ashes were dumped into the river. I did not find this out, however, until many decades later.

Hunger, fear, illness and death ruled Theresienstadt at all times. In the autumn of 1944, two huge transports left Theresienstadt for the East. As I now know, but did not know then, they went to Auschwitz. The people in those transports were never heard from again.

On May 8, 1945, Theresienstadt was ‘liberated’ by the Russians who were on their way to somewhere else and happened upon Theresienstadt. This was the way in which most concentration camps were ‘liberated’.

But what liberty? Who knew what we would find when we returned home or searched for relatives and friends? Who knew whether we would find any of our possessions? Mostly we found nobody and nothing; all family and friends had been murdered in the death camps.

(…)

Eventually, on June 25, 1945, we were taken, by truck, back to Amsterdam, back to Central Station. There we learned that our pre-war upstairs neighbors, the Van den Berg family (mother Trien, father Wim, and their two daughters, the elder daughter Willy, and the younger one, my best friend Carla), had left word that, should we come back, they would take us in. So that’s where we went. We stayed with them for about a year. After that year, we were able to rent the same apartment that we had had before the war. I had just turned twelve after liberation and I had to go back to elementary school where I was put in fifth grade. My father went back to work and life became ‘normal’ again. Only, of course, life was never normal again!

I could never talk to my parents about the war and the years in the camps. I could never ask questions about the people who had disappeared. Many of us, children and adults alike, could never talk about what had happened to us. We could not ask questions. We could not discuss it. People did not want to hear about it. Nobody wanted to listen. It was, and often still is, the ‘great silence’.

We all had and have too many scars, both psychologically and physically. Most of us survivors have them. For us the war will never be over.

Ruth Gabriele Sarah Silten

Pomona, California